My Weapon of Choice

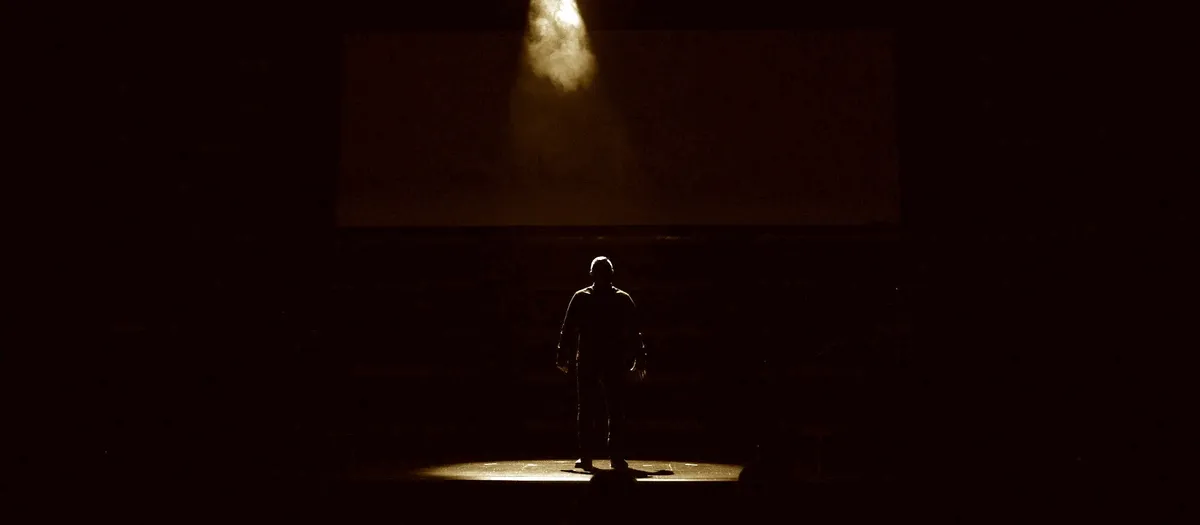

It's midnight, and I’m communing with Christopher Walken again. I repeat the line, and it comes out differently.

Anyone who's ever been complimented on a halfway decent celebrity impression eventually finds themselves at the milestone of attempting a Walken. But let me be clear. This is not a hobby. This is not a party trick in development. It's a kind of possession. A force takes over, and suddenly the most important thing in the world is catching that off-balance rhythm, exactly wrong.

This ghost first grabbed the wheel in college. A ten-page paper on the spiritual gentrification of Augustine's City of God was due the next morning, and my friend Vishal and I were supposed to be locked in, churning out brilliance. Instead, a strange compulsion took over, and our focus dissolved into manic energy - the kind that accomplishes absolutely nothing. An impulse to turn the wheel of the car head-on into traffic.

There were strategic runs for mozzarella sticks. There was Ronnie James Dio - soaring, campy metal played at a volume that chased every productive thought out of the room. There were sets of pushups to stay awake, which eventually blended with the music until we were belting out, "Doing pushups in the dark!" over a Dio chorus. It was mutually assured distraction.

And then there was the gold watch. In that state of adrenalized panic, my brain sought a different kind of intensity. Instead of writing the paper, I was seized by the critical need to re-watch Pulp Fiction. I placed the DVD into my desktop tower, next to my irresponsibly large CRT monitor, a sixty-pound relic I purchased shortly after the Y2K scare fizzled out.

When I got to the gold watch scene, I was mesmerized by the strange, hilarious, and slightly threatening man on the screen. Never mind that dawn was coming on, and behind the movie window, the Microsoft Word cursor winked at me like it knew just how doomed the paper was.

For years, I filed that incident under "Procrastination, Classic."

A decade and a half later, after years spent building things in the startup world - first my own, then other people's - I was out. The work had been both electric and exhausting, narrowing my world to a single point of focus. Finally, I had some financial security, and I was ready to take a breath.

Which is how I ended up at a dinner hosted by a well-known venture capitalist. The room was full of people who’d either just started something, just sold something, or were manifesting their next thing. It was a culture built on a devout hopscotch from one venture to the next, forever trying to change the world - or at least be loved for making the attempt. Everyone spoke like they were late for their own TED Talk, following the same script, hoping for a better third act.

The host cornered me, all charm and microdosed optimism, and asked what excited me these days. I told him I’d been reading about psychotherapy - specifically this “parts work” model, the idea that we’re made up of conflicting inner characters, each trying to help in its own way.

As I spoke, he seemed fascinated, and then asked, “But how do you scale it?”

My smile held, but my stomach tightened. Inside, an exasperated voice screamed, "You don't scale it." I suddenly felt like I was trying to describe a color he couldn't see.

I replayed the conversation on the drive home. How do you scale it. How do you scale it. The question became a judgment on any activity that didn't obey a growth curve. How do you calculate the ROI of a summer day?

Hoping for an answer, I attended an entrepreneurs' circle to discuss what's next. We sat around a conference table in a brightly lit co-working space that smelled like fresh espresso and new furniture. One guy was disrupting HR. A woman wearing an entire gauntlet of fitness trackers on her wrist was putting mindfulness on the blockchain.

When it was my turn, I admitted I was exploring. Taking time to figure things out. The nods around the table were understanding, but a couple of people looked at me with vague concern, like I had shown up with a troubling mole on my face - probably nothing, but something I should really get checked out. "You should read about ikigai," one person offered. "There's a retreat in Tulum that's completely life-changing," said another. The subtext was clear: even rest had to be productive. A stepping stone to the next achievement, part of the push to cultivate a "growth mindset" (which, when you think about it, tumors also have).

I sat there, looking at these people sprinting toward their next acts - angel investments, new startups, spiritual retreats that were somehow also startups - and their well-intentioned concern felt like a verdict. I was a problem to be solved. So, I tried to solve it their way. I ran Tabata intervals, trying to bio-hack my way to clarity. I turned my life over to a dashboard where my humanity was measured in sleep scores, step counts, and blueberry intake.

Each metric, another step on the striving treadmill - that relentless, chirpy pressure to always become something else. Couldn't I ever just be?

Defeated by my own dashboard, I found myself in a coffee shop when two guys at the next table started talking in that breathless startup cadence: TAM, CAC, LTV, platform, flywheel. Synergies. The words washed over me like a language I used to speak fluently but could no longer remember why. A wave of exhaustion hit me. The wall color suddenly seemed wrong, like I'd wandered into someone else's house.

What language did I speak as a boy?

And then, it happened again. The old possession. I could feel it taking shape - like a jingle you don’t remember learning but somehow know all the words to. A line from Wedding Crashers slipped out of my mouth, half-mine, half-his.

An a-Walken-ing.

That night, I started watching everything. My browser history became a fever dream of Walken research - interviews, dancing compilations, obscure talk show appearances from the '80s. I practiced in the car at stoplights, catching my own eye in the rearview mirror mid-sentence, studying his rhythm like I was preparing for an exam. Once, the guy in the next lane looked over. I gave him a nod.

I read an interview where Walken said that he removed all the punctuation from his scripts, treating the lines like sheet music instead of sentences. I read that. About the... punctuation. And I thought. Wow. There it is. The key. I had to unlearn... grammar. I’d paste his monologues into a text editor, strip them of commas and periods, and find the rhythm by ear, like a jazz student learning a solo.

It was a rhythm that defied convention. Contrapuntal. Syncopated. I'd spend hours trying to nail the elastic pacing of a single sentence, stretching one word until it wobbled, and snapping the next like a rubber band. My parents, with their conservatory training, would be proud I'd finally found my instrument: Walken’s voice, played badly but with feeling.

The practice became oddly systematic. I'd record myself, play it back, wince, try again. Hours would vanish. Then one evening, I caught myself about to create a spreadsheet tracking different Walken character types, and I had this moment of recognition: Oh god, I'm treating this like work.

Except I wasn't. Not really. When I worked, there was always this background hum of anxiety - that I should be further along, that someone else was moving faster, that I was falling behind. But this? This was just fun. Pointless, obsessive, private fun. I'd practice a line twenty times not because I should but because I wanted to hear if I could get the rhythm to wobble in just the right way.

The real genius was in his pivot - the way he could turn from menace to levity in a single, off-balance phrase. Learning how to whiplash like that became my new obsession. I had a fever, and the only prescription was more Walken.

One night, I queued up Pulp Fiction again. Captain Koons appeared on screen, telling young Butch about the watch. Here was this strange, hilarious, and slightly threatening man, delivering a monologue about the indignities of war, and suddenly the VC's question echoed in my head: "But how do you scale it?"

I pressed pause. The juxtaposition was so absurd it was clarifying. You don't scale this moment. You don't optimize it. The entire point of its power is that it's unscalable, unrepeatable, and utterly committed to its own weird, magnificent truth.

Just like in that dorm room, it felt like I'd been given secret permission to burn the assignment. The freedom was intoxicating. In that flash of heat, I finally saw the bars of the cage I had built for myself. What good is a truth you can't measure?

The force that had been grabbing the wheel all these years revealed itself. Not a hijacker - a script doctor. A brilliant, annoying script doctor who couldn't just hand me a note that said, "This scene is lifeless." No, he had to get on stage, mid-performance, and start doing a bad celebrity impression just to show me the script was killing the actor.

The point was never to be Christopher Walken. Doing the impression wasn't productive, it wasn't scalable, and frankly, it wasn't even that good.

The point was the practice - the pointless, obsessive, private fun of it. The practice was the message - his only way of saying, "This story you're writing for your life? It needs more joy. It needs less punctuation. It needs more cowbell."

Two months later, I attended another founder dinner. Different host, same energy - the usual cast of next-act founders swapping insights. Midway through the appetizers, someone asked what I was working on these days.

Immediately: that familiar tightness in my chest, the sense that I needed a good answer, an impressive answer. The old programming flickered to life, ready to offer a sanitized reply about "quantified ideating at the intersection of performance and personal growth."

And then, underneath that, I felt something else rising. The script doctor, clearing his throat.

"I've been practicing my Christopher Walken impression," I said.

There was a beat of silence. Someone laughed, uncertain if I was joking. The guy next to me asked if I was serious.

"Completely serious," I said, and then added, in a growl, "Every once in a while, the lion has to show the jackals who he is." It wasn't perfect, but it was pretty good. A couple of people laughed. One guy said, "That's actually not bad." And for the first time in a room like this, I realized I didn't care if it was.

The conversation moved on to seasteading.

The treadmill was still humming, but I wasn't on it. I was standing next to it, watching it whir, occasionally hopping on if I felt like it, but no longer believing it was the only way forward.

Now, when that familiar compulsion rises, I don't see a saboteur. I see my script doctor clearing his throat.

And I know it's time to ask what's wrong with the script.